There’s been a lot of discussion this week about food dyes and whether they should be removed from U.S. food products, following a recent statement from the Department of Health and Human Services. As I was preparing to write about this issue, two people whom I highly respect offered highly informative perspectives on the topic: Dr. Susan Mayne, former director of the Center for Food Safety and Nutrition (CFSAN) at FDA, and Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist and a great communicator. So, rather than paraphrase their excellent comments, I decided (with their blessing) to combine them into a composite.

My purpose here is not to take a position on exactly what decisions should be made about artificial dyes and food. Instead, I hope to provide some perspective about what we actually know about these products and to outline what I hope will happen to sort out the questions surrounding these and the many other substances that will need to be evaluated in the future.

I’m chiefly concerned that the development and public rollout of policy based on slogans like “getting rid of petroleum” and “not allowed in Europe” is inadequate for dealing with issues that are really not so simple. What would be much more helpful would be to see a clear, transparent summary of the evidence and public discussion of a plan for managing any needed changes, including considerations of feasibility and costs.

In other words, there is some rationale for the system that is in place for federal agencies to make major policy decisions. While I agree with those who claim that it has become too burdened with bureaucracy, the fundamental requirement that government should show evidence that supports an action within the substance of the law is sound. Furthermore, the requirement that government should publicly consider the implementation plan, including the effects those changes will have on people and on different parts of our vast economy makes sense. This kind of work requires expertise from a team of scientists, policy makers, economists and legal experts at the least.

Here's what Dr. Mayne had to say:

“What’s up with petroleum-based? When Secy Kennedy hosted a press conference about synthetic food dyes the term “petroleum-based” was used repeatedly by many speakers, with RFK Jr. admonishing consumers that “if they wanna eat petroleum, let them do it at home.” This was seemingly in reference to FDA-approved and certified food dyes that are manufactured using substrates derived from petroleum. Petroleum has been the main source of hydrocarbons used as raw materials to synthesize chemicals for over a century. Numerous products in our everyday environment use petroleum hydrocarbons as part of their synthesis. But the MAHA movement has demonized “petroleum-based” (or petrochemical) as meaning unsafe, especially for our children.

“What else is derived from petroleum hydrocarbons? Many things, but one thing the MAHA movement has been silent on is synthetic dietary supplements. Yes, many dietary supplements are “petroleum-based” and are incorporated into numerous fortified foods and supplements. While some are derived from natural sources, there are a large number that are not. Take vitamin E for example. D-Alpha-tocopherol is the natural form, DL-alpha-tocopherol is synthetic. Natural & synthetic forms can be esterified (which is a chemical reaction – i.e. synthetic) to make products like alpha-tocopheryl acetate & alpha-tocopheryl succinate. Succinate is often derived from petroleum as well, so even if the vitamin E parent molecule itself is natural, it can be modified using synthetic chemistry, often with petroleum-based substrates. So when you are taking a vitamin supplement, are you “eating petroleum at home”? Many MAHA influencers profit from selling dietary supplements, so where is their outrage for those that are made from petroleum-based substrates?

“For those products that are marketed as being derived from “natural” sources, when it comes to vitamin E, one primary source is “seed oils” such as soybean oil or sunflower seed oil that MAHA has also stigmatized (seed oils are a great source of vitamin E, as well as essential fatty acids but I digress here).

“What about vitamin C? Ascorbic acid can be from natural sources (e.g., rose hips) but often is obtained from “chemically processed sugar” (the other “poison” Secy Kennedy attacked during his press conference).

“To be clear – I do not believe petroleum-based synthetic dietary supplements are unsafe (at exposures below established limits). But, the hypocrisy is clear: attack petroleum-based synthetic dyes (eating petroleum!), while market and sell dietary supplements that contain petroleum-derived ingredients, ingredients derived from sugar, and ingredients derived from seed oils (all poison per RFK Jr.). Consumers deserve to be informed and engaged but not deceived about ingredients in their foods and dietary supplements.”

And here’s what Dr. Jetelina had to say:

“Red dye #3 is already out the door, and the new HHS administration is trying to phase out the rest. Last Tuesday, HHS announced the initiative.

What actually happened:

Only two rarely-used colors—Citrus Red 2 and Orange B—were officially revoked.

For the remaining six, which are more widely used, it will be entirely up to the food industry under a voluntary “understanding”—not a formal ban. Response from industry members so far has been mixed; some have pledged support, while others are maintaining their safety.

Some key context:

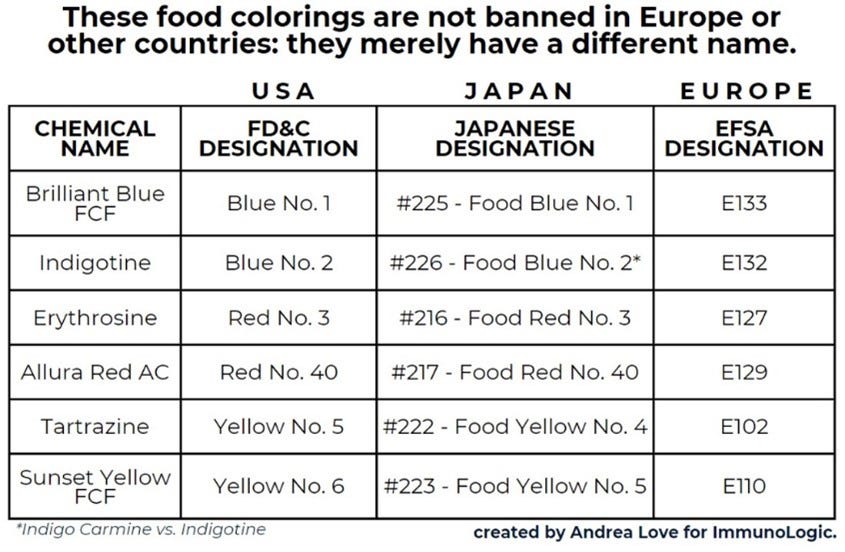

Contrary to popular belief, five of these six colors are allowed in Europe whose regulatory body follows a more cautionary hazard-based approach to food safety. They just use different names on their food labels. Dr. Andrea Love created a great table (see below).

Possible tradeoffs: Natural colors are generally less vibrant and may help reduce the appeal of unhealthy foods to kids. It will be interesting to see the impact on consumers. But natural colors are also more expensive to make, less consistent (affected by pH, cooking and processing) and less shelf-stable—which means higher food costs and potentially more food waste. Some natural colors may also pose a risk to individuals with food allergies, making transparency in ingredient labeling critical.

What does this mean for you? It’s unclear at this point. The impact on you as a consumer will depend on how—and whether—the industry chooses to shift. But again, let’s not lose the forest for the trees. For real progress to make America healthier, we need a number of systematic changes that tackle root causes.

As you can see from their summaries, Drs. Mayne and Jetelina do not see removal of these food dyes as a clear-cut winning policy. The good news is that consumers will not be hurt if dyes are removed, and some adverse behavioral effects may be prevented. But while I’m glad that the issues of chemical additives in our food and healthy nutrition has been raised in the public consciousness, I hope that the administration and Congress will invest in qualified scientists to evaluate the available data, design and fund research to fill gaps in knowledge (there are many of these), and produce reports for a valid societal evaluation, rather than cutting key scientific capacity and reverting to ‘policy by slogan.’

Getting rid of petroleum-based food dyes will not hurt health, but many pending decisions could have major consequences if they are slogan-based rather than evidence-based.